When You Hand Someone a Gun, Make Sure You Know Where They are Going to Point It

As an architect and urban planner, my focus is always, first and foremost, on creating spaces for people. That focus is filtered though a myriad of lenses, economics, client direction, etc., but the goal is always the same. As most are aware, the U.S. experienced an explosion of growth after the second world war, and with the automobile as an affordable mode of transit, the nation’s urban structure burgeoned into what we now call the suburbs. Zoning models followed this, regulating land use in a way that abandoned traditional walkable communities in favor of automobile-centric circulation. In the last few decades, however, there has been a growing movement of communities embracing Form Based Codes. Unlike traditional zoning “Form Based-Codes (FBCs) seek to restore time tested forms of urbanism. They give unity, efficient organization, social vitality, and walkability to our cities, towns and neighborhoods.” (via the Form-Based Codes Institute)

Trust me. You want this. If you’ve ever tried walking somewhere and cursed that there wasn’t a sidewalk and fought with cars zipping by, or stared blankly at the sea of empty asphalt in front of a big box retailer…then you know what this is trying to fix. The poster child for FBCs are quaint European or east coast urban cities, with walkable streets, al fresco dining, and unique shopping, all knitted together with a family urban conditions that shape the space into more of an outdoor room than just the “street edge”. In general terms, good FBCs regulate the amount and location of parking (more off the street and into parking garages rather than huge lots), building heights and proximity to the street (certain proportions just work better than others, based on human scale and perception) and how those buildings address the street (provisions for openings, entries, shade, awnings, etc.) It should be noted that an FBC is distinctly different from any sort of historical design standards which seek to preserve the architectural character and scale of a historical area. It is about the form, not the style.

Professionally, I’ve navigated FBCs for over a decade, have been party to writing a few myself, and was even fortunate enough to participate in an advisory role for the crafting and implementation of a FBC in my own community. There are good ones and bad ones, and You see, at it’s core, an FBC is legislation…legal guidelines. Traditional land use zoning has largely ignored the ramifications of it’s guidelines on the health and welfare of people, because just about anything, any design, good bad or ugly (and all too often they are very ugly) can happen. FBCs, therefore seek to elevate the floor of design, by requiring minimum standards for how the building can be interacted with, engaged and used.

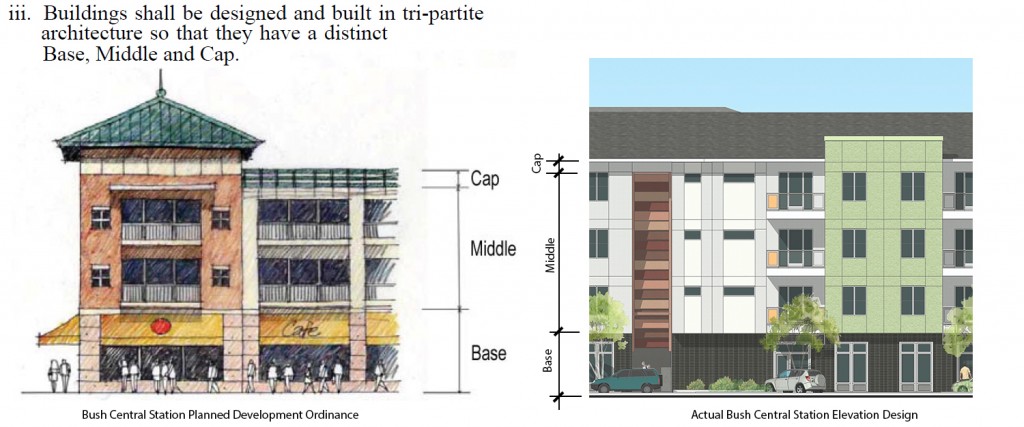

What we are increasingly coming up against, however, are cities who don’t really understand how a FBC should be used, or are intentionally using them outside of this intent. One of the big problems is the very word “code”. Building codes are purposefully inflexible and try to limit varied interpretations. A good FBC however is a guideline to facilitate, not dictate. However, for many cities if it’s in the code, IT’S IN THE CODE. If it’s there, it has to happen, and that’s what makes prescriptive design elements so dangerous. For example, we have a project where the master developer (not our client) wrote the FBC with little or no input from city staff. Staff has taken the interpretation, therefore, that they have no choice but to inflexibly enforce the letter of the code, in the same manner that they would a building or fire code. In this instance, the code item that gave us heartburn was the tripartite arrangement:

As you can see, the design the client wanted was not a traditional “style” and was never intended to follow the rules of classical design. This is an up and coming market that is trying to appeal to a younger generation or urbanites who seek to interject themselves into the progressive, the interesting, the unique. Where they live, and what they live in, is often as important as what they wear or drive. The design caters directly to this.

We went back and forth with the city, trying to separate the intent of the code from the letter of the code. They loved the design, but their hands were tied, the code wanted base, middle and top, so we had to add a heavy stucco frieze board. The client didn’t want it, we didn’t want it, the city didn’t necessarily want it, but it’s in the code, it has to happen.

We ran into another issue with this same code which read “Corner emphasizing architectural features, pedimented gabled parapets, cornices, awnings, blade signs, arcades, colonnades and balconies may be used along commercial storefronts to add pedestrian interest.” What this became, by their interpretation, was a requirement to have a “tower” element at every corner of the building. This is a knee-jerk reaction that I’ve fought against much of my career. I’m just as guilty as anyone, I use towers to turn a corner with the best, but it isn’t the only solution. What happens all too often is a systematic repetitive response that does little to address the uniqueness of a site and while technically complying, does little to enhance the user experience.

Image via Google Street View

Image via Google Street View

This morphology, for me, always invokes the towers of castle architecture of the past. Design is always subjective, but there must be leeway in the code and it’s interpretation that frees the architect to engage different ways of thinking, attend to singular conditions, without simply designing with a brick-a-brac kit of architectural parts.

This sort of reliance on verbatim historicism reminds me again of the trite, but unfortunately still quite relevant, statement the Dean of Architecture spoke to the quintessential architectural protagonist Howard Roark:

“You must learn to understand–and it has been proved by all authorities–that everything beautiful in architecture has been done already. There is a treasure mine in every style in of the past. We can only choose from the great masters. Who are we to improve upon them? We can only attempt, respectfully, to repeat.”

Ayn Rand, The Fountainhead (1943)

That’s right. I pulled out the big guns. It’s cliche, but in so many ways it’s sadly true. We must fight this.

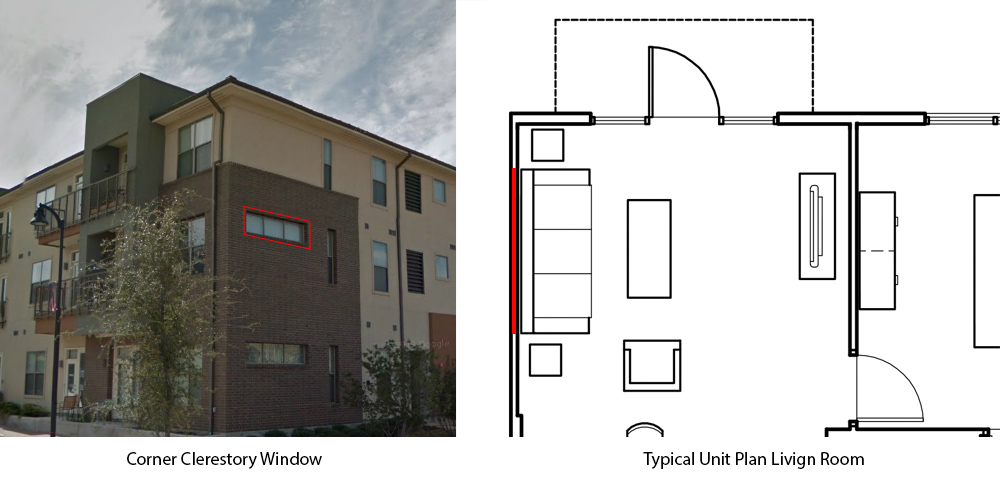

In an even more recent example, the FBC reads, quite clearly “windows will be oriented vertically and utilize distinct frames, materials or colors for window surrounds.” I’m honestly not sure of the reasoning behind why windows must be vertically oriented, other than with the express goal of more traditional design, to the exclusion of the contemporary. The issue there is any regulation limiting the creativity of the design, can also limit the quality of the design. Here is one of my favorite responses to a particular problem we face quite a bit with residential units:

Typically units face outward, and have glazing or balconies oriented that way, and as you can see, when we have a unit on an outside corner, there is an opportunity to get light into that space. The problem comes up with full height windows, because you lose a wall to put you couch against, or you have to put your couch in front of the windows. By employing a horizontal clerestory window, the architect can get more light into that space, and preserve the couch wall. With a code that prevents this sort of flexibility, there can be an infinite variety of innovative solutions that never come to fruition. In this instance, the solution is to remove the window, so there is a blank wall, less light, and everyone loses.

Typically units face outward, and have glazing or balconies oriented that way, and as you can see, when we have a unit on an outside corner, there is an opportunity to get light into that space. The problem comes up with full height windows, because you lose a wall to put you couch against, or you have to put your couch in front of the windows. By employing a horizontal clerestory window, the architect can get more light into that space, and preserve the couch wall. With a code that prevents this sort of flexibility, there can be an infinite variety of innovative solutions that never come to fruition. In this instance, the solution is to remove the window, so there is a blank wall, less light, and everyone loses.

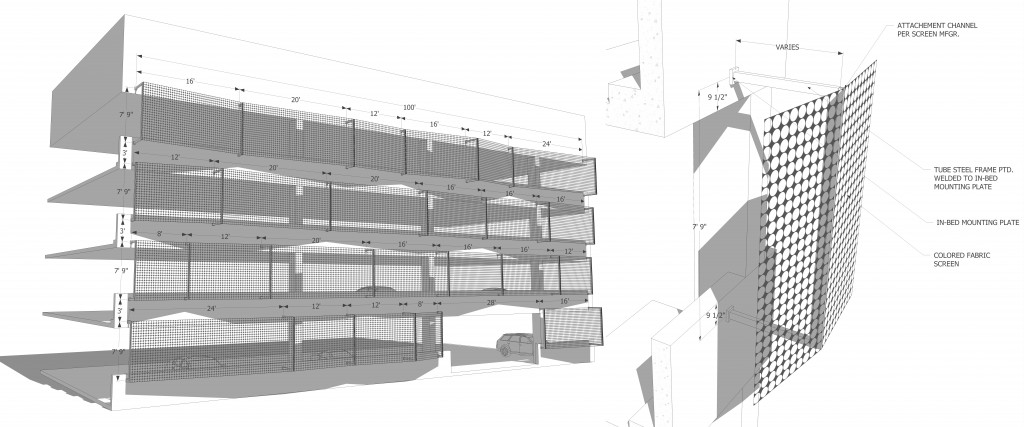

Another code prescribed that the “At least 12 percent of the parking structure facade (including openings, if any) must be covered with the same material used predominantly on the first 24 feet of height of the main non-parking building..” Clearly, this was an attempt by the code writers to prevent huge, blank, parking garage walls from marring the urban landscape, and rightfully so. We hit this problem with a 7 story mid-rise project where the the garage was integrated within, but had edges that fronted the street. A basic rule of garages is that they legally need ventilation, either by being largely open or through mechanical means. As designers, we prefer natural ventilation, however, as it also allows in light and leads to a substantially better experience overall for the user (and is, in fact, cheaper than the mechanical option). Following this logic, we embarked on a design that included an undulating colorful fabric screed that would screen the cars but allow in air and light while offering a dynamic form at the street level:

In this instance, the reviewer couldn’t move past the letter of the code, and because this fabric screen we were suggesting did not occur anywhere on the rest of the project, it was disallowed. As a result, we wallpapered the adjacent brick along a side portion and met the goal of the 12% required.

In this instance, the reviewer couldn’t move past the letter of the code, and because this fabric screen we were suggesting did not occur anywhere on the rest of the project, it was disallowed. As a result, we wallpapered the adjacent brick along a side portion and met the goal of the 12% required.

Now, in this instance, I frankly really like the subtle exposure of the parking. The parking is just a component, a gear or cog in this machine for living in. Seeing it as an essential and utilitarian part of the whole is frankly rather truthful and beautifully honest. That said I believe a strong case is to be made for rather having the more substantial dynamic screen, especially at the street level.

The point here is in how an FBC can aspire to do good, but if clumsily implemented, at best, limits creativity and innovative design, and at worst, becomes a tool for empowering those who should not necessarily have input into the design that shapes the built environment. While working on the committee for my local FBC, I literally had a city councilman (lawyer by trade) bluntly state to me:

“I want to limit the architect’s ability to color outside the lines.”

So many factors shape a design, from very subjective desires by the owner or the architect, to very objective ones like the program, market conditions or site constraints, that there are an infinite number of solutions possibly and simply cannot be rigidly prescribed. The goal of an FBC is to elevate that end product, first by obliterating outdated zoning that torpedoes it, and second, by elaborating a clear framework within which design can freely maneuver, and achieve a healthy urban outcome. It should never be used to enforce a myopic or binary personal objective for the development of our cities.