Crafty

Liberal Arts colleges are struggling. There are several articles that have been written on the demise of the liberal arts colleges and why students are chosing more targeted career driven curriculum. It is a symptom of, what believe, to be a crisis in higher education in which college is being viewed less and less like “higher education” and rather more like a vocational training for higher paying jobs.

What does this have to do with architecture? Well, as a profession we’ve been struggling for years with a debate concerning our own relevance. In response to this, I believe architecture schools have begun to fall into the same trap, tailoring their curriculum not to graduate critical thinkers in the built form, but cogs in the architecture machine. I feel this is an incorrect assumption. And I’m not the only one.

“Architecture education should be unapologetically vocational in its ethos, not for training purposes, but concerned with lifelong learning and the practice of the next generation of architects. Those who envisage an architectural destination and can articulate built form of human life, deserve the title ‘Architect’, and those who have it, or wish it, are urgently required.”

-Christopher Platt, Professor of Architecture at the Mackintosh School of Architecture, Glasgow (2014)

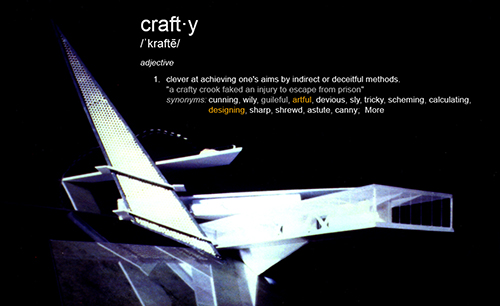

With colleges focusing more and more on simply getting a job, we’re debasing professions at large, and robbing society of a level of critical thinking that cannot be replaced. While there is certainly a craft to the profession of architecture, a excellence in the skill of making buildings, there is more than just the ability to execute involved in good design. I was interested to find that the very definition of “crafty” bore descriptors like “design” and “artful” whereas just the raw meaning of “craft” is simply relegated to more of a “skill”.

I’ve been interviewing and hiring young professionals for nearly a decade, and over the years I’ve seen a noticeable decline in this “craftiness” candidates bring to the table once they work for us. Many have incredible portfolios that sing with crisp renderings and beautifully seductive designs. They’ve been trained very well to master the softwares and presentation techniques, but they fall apart with even the most basic levels of critical thinking.

My favorite, when presented with a presentation board or some other deliverable, is to ask them “If your final studio grade rested on what you have here, would you submit it just like it is?” Often there are silly mistakes, the wrong date, spelling errors, etc. but that’s not what I’m talking about. What I really want to know is if they put their design soul into what they are giving me. Are they passionate about the result, have they explored all reasonable alternatives, do they honestly believe that what they have generate is the best thing for the client, and the best thing this form can produce?

I love it when colleagues second guess me. I love the discourse that follows. Sure, sometimes opinions cannot be reconciled, and it comes down to “do it because I said so” but that is very, very rare. Typically, those conversations lead down really interesting avenues of discovery, and almost always end up with a better design for the client. To that end, there is a craftiness in architecture that moves well outside the realm of simply adhering to a “program”. Anyone who has taken the NCARB graphic exams knows, you can solve for a complicated program by cobbling together a terrible design. It may be technically correct, but that doesn’t mean this is what is best for the client.

What I fear is the easy path cloaked in beautiful trappings. It feels like much of the work I see from new graduates gets the problem solving out of the way, then looks for a post rationalization for the exterior trappings that justifies a form they find appealing.

I love process sketches. Increasingly I’ve delved deeper and deeper into the portfolio of prospective employees to see how they think, not just what they produce. Frankly, with the prolific access to software, beautiful renderings have become too easy. They are a poor representation of how a graduate thinks, how they solve problems, what rigor they go through to achieve their ends. While this has always been true, I see them less and less. Often this is because students rarely sketch anymore, or build study models, or really explore multiple ways of looking at a problem. They find a big idea, they dig up an architect’s work to emulate, and they synthesize the two in a sexy rendering.

There is no craftiness there.

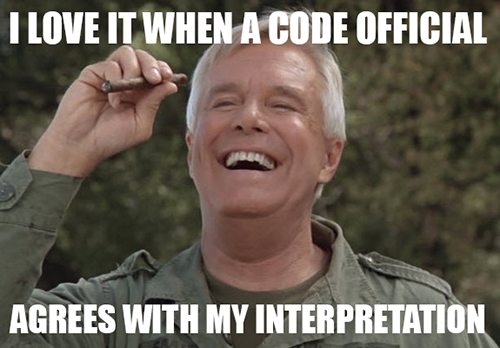

There is a craftiness in design. There is a craftiness in working with contractors. There is a craftiness in interpreting the code. It’s easy to find reasons why you can’t do something, but much more difficult to find ways that you can. I’ve found myself having to teach young professionals to simply second guess, to critically analyze and to really think about what they are designing. The beauty of what we do is there’s no set of stereo instruction on how to make a good design. If you give five different architects a problem, it’s fundamentally beautiful that they’ll come up with five different solutions, and each may be just as valid as the other.

Craftiness is rarely sexy. Craftiness is found in convincing a code official in an interpretation that allows the architect to solve a problem they couldn’t otherwise. Craftiness is found in the unconventional use of a material that meets the performance goals, the price point, and the aesthetic concerns. Craftiness transcends the “craft” of simply building, and makes it architecture.

Losing this is part of our profession’s struggle with relevance. Contractors can “craft” buildings, but it is a good architect that is crafty enough to solve the program, come in under budget, and deliver a design that doesn’t just work, but enhances the human experience.

We need more crafty architects.

+++

This post is part of a coalition of architects posting on a single topic, each interpreting it in their own way. If you’d like to explore their thoughts on the same topic, I encourage you to follow this links below:

“Bob Borson – Life of An Architect @bobborson Architects are Crafty“

+

“Matthew Stanfield – FiELD9: architecture @FiELD9arch On the Craft of Drafting: A Lament“

+

“Marica McKeel – Studio MM @ArchitectMM Why I Love My Craft: Residential Architecture“

+

“Jeff Echols – Architect Of The Internet @Jeff_Echols Master Your Craft – A Tale of Architecture and Beer“

+

“Lee Calisti, AIA – Think Architect @LeeCalisti panel craft“

+

“Mark R. LePage – Entrepreneur Architect @EntreArchitect How to Craft an Effective Blog Post in 90 Minutes or Less“

+

“Lora Teagarden – L² Design, LLC @L2DesignLLC Oh, you crafty!“

+

“Rosa Sheng – Equity by Design / The Missing 32% Project @miss32percent Which Craft?“

+

“Michele Grace Hottel – Michele Grace Hottel, Architect @mghottel krafte“

+

“Meghana Joshi – IRA Consultants, LLC @MeghanaIRA Crafty-in Architecture as a Craft“

+

“Stephen Ramos – BUILDINGS ARE COOL @sramos_BAC Ghost Lab“

+

“Brian Paletz – The Emerging Architect @bpaletz Underhanded Evil Schemes“

+

“Eric Wittman – intern[life] @rico_w arts and [crafty]“

+

“Cindy Black – Rick & Cindy Black Architects merging architecture and craftiness“

+

“Tara Imani – Tara Imani Designs, LLC @Parthenon1 Crafting A Twitter Sabbatical“